Across the U.S. a growing number of seniors are moving to cohousing communities, which are designed to foster social interaction and ward off loneliness and isolation. Read Transcript

Benefits of Senior Cohousing Communities

It's no secret that loneliness and isolation can be harmful not only to our mental well-being, but also our physical health. In recent years researchers have labeled loneliness an epidemic, with health risk rates similar to those for obesity and smoking 15 cigarettes a day.1 And seniors are among the segments of the population most susceptible to loneliness and isolation due to such factors as their kids moving away and lack of mobility.

In the U.S., though, a growing number of seniors have found a new way to combat loneliness and social isolation: cohousing.

Though the designs and layouts of cohousing communities vary, the most typical format is individually owned homes with common areas created to get residents interacting as much or as little as they want. These socially focused common areas can include the common house - or clubhouse - where residents can gather for community meals several times a week, vegetable gardens, or courtyards where happy hours might take place. Typical shared amenities include rooms for laundry, exercise, mail delivery, computer use and TV watching. These shared spaces both encourage interaction and keep costs down.

According to the Cohousing Association of the United States, also known as CohoUS, some of the principles of cohousing are:

- The community is designed to foster connections. Physical spaces allow neighbors to easily interact with others just outside their private homes. Common areas like kitchens, dining spaces and gardens bring people together.

- Common property is managed and maintained by community members, and collaborative decision-making builds relationships.

- Connecting with the community is easy and natural, but not required or constant. Cohousing cultivates a culture of sharing and caring, but privacy matters, too.

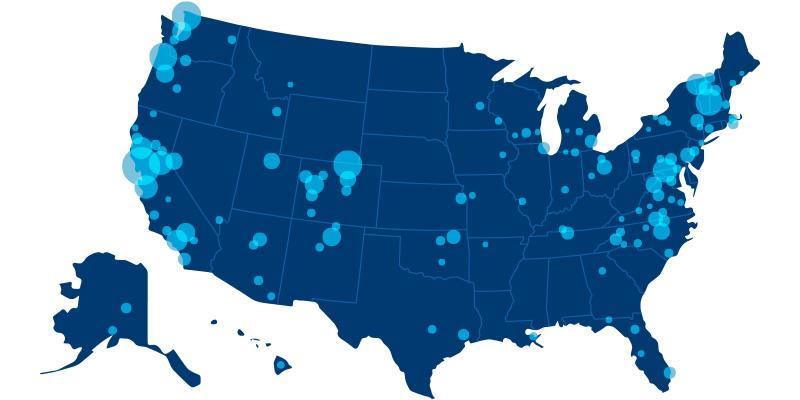

CohoUS says there are about 170 active cohousing communities across the country, with roughly 140 more in the planning stages.

Most cohousing communities are designed and built from the ground up by a group of people with a shared vision of community who then work with architects and developers to bring it to life. A smaller number of the existing cohousing communities in the U.S. are retrofit models where residents have adapted existing buildings or sections of neighborhoods. The idea took root in the U.S. in the 1980s, inspired by a community in Denmark.

Studies support the notion that cohousing can ward off the ill effects of loneliness and lack of interaction. One researcher, Vivian Puplampu, wrote in the Journal of Aging and Environment in September 2019 that cohousing positively impacted healthy aging in place "by preventing social isolation, providing informal services, security, independence, and improving older adults' quality of life."

Of the 170 or so existing cohousing communities in the U.S., around a dozen are restricted to seniors ages 55 and older. The rest are multigenerational, meaning anybody can live there. Many seniors prefer to live in multigenerational communities, where their neighbors may range from babies to people 80 and older, according to Dr. Angela Sanguinetti, director of the Cohousing Research Network.

"Both are great models," says Dr. Sanguinetti. "Some people want to age in place with kids, and others just with people their age."

But Dr. Sanguinetti points out that senior-only communities are the fastest-growing sub-segment of cohousing. The mutual support among neighbors that's typical in cohousing has a special appeal to seniors who wish to safely age in place. "You see your neighbors regularly and know who is coming and going," she says. "Just as important is noticing when a neighbor you normally interact with is suddenly not around. They might need to be checked on."

Here's a look at a few cohousing communities and what residents have to say about communal living.

Silver Sage Village

Alan O'Hashi knew little about cohousing in 2008 when he moved into Silver Sage Village, a senior community in Boulder, Colorado, a move he says was steered mostly by his partner.

It wasn't until O'Hashi, now 67, nearly died from pneumonia in early 2014 that he finally got it. "That's when I figured out it was about this intentional neighborliness," he says. "All of a sudden people started calling up and bringing in food. That was my introduction...it was like getting my visit from the ghosts of Christmas yet to come."

Now president of the CohoUS board, O'Hashi, a documentary filmmaker who has made five films about cohousing, keeps an office in the 5,000-square-foot common house, which includes an industrial kitchen; a dining room; rooms for crafts, exercise and meditation; and spaces used by local artists.

O'Hashi says being in this community during COVID-19 has been a blessing. "With everyone over 60, we are in a vulnerable category. Many have preexisting conditions."

In a regular community people say, "Give me a call if you need anything." In cohousing, if you need a cable jump, it's "I'll be right over."Alan O'Hashi

Silver Sage was "way ahead of the curve" when the pandemic hit, according to O'Hashi. One of the residents, a registered nurse, got things going as early as February with meetings on the subject, and the residents came up with protocols for mask-wearing and social distancing. The common house and garden are still closed to outsiders due to COVID-19.

O'Hashi says "the secret sauce" of cohousing is the simple expectation that everyone be good neighbors: "In a regular community people say, 'Give me a call if you need anything.' In cohousing, if you need a cable jump, it's 'I'll be right over.'"

Wild Sage

Karin Hoskin is among the 84 residents of Wild Sage, a multigenerational cohousing community across the street from Silver Sage Village. She compares her cohousing community to living in a small town where everyone knows each other.

"It was about how we wanted to raise our family," says Hoskin, 50, executive director of CohoUS. Her household includes her husband, 58, two teens, and her 88-year-old mother-in-law - the oldest member of their community - who moved in seven years ago due to flooding at her home and liked it so much she stayed."

When people ask what it's like raising her kids there, Hoskin tells of the time when her daughter, 15, had friends over. As the teens walked to the common house about 50 yards away to watch TV in the cozy media room, her daughter stopped three times to chat with neighbors. By the time they got to the common house, one of the friends asked, "You know all of your neighbors?" "Yeah," Hoskin's daughter replied. "Don't you?" "No!" said her friend.

Bryan Bowen, 48, moved to Wild Sage 16 years ago and lives there with his wife and two teenage sons. He was an architect on both Wild Sage and Silver Sage Village and is currently working on a number of other cohousing communities. He calls cohousing "the future."

"Americans have been suffering from a high level of alienation and isolation, exacerbated by social media and urban planning trends," he says.

Bowen says that baby boomers don't want to be a burden on their children, and cohousing offers them a way to age better in place. "When you lose your spouse, you have someone around you," he says. "When you become ill, you have people who will bring you dinner and sit with you."

PDX Commons

Gretchen Brauer-Rieke, 63, lives with her husband in the PDX Commons senior cohousing community in Portland, Oregon. Home is a four-story, 27-unit “urban chic” building four miles from downtown Portland with plenty to do within a quick walk. She likens her neighbors, all age 60 and over, to siblings: not all people you'd choose as friends but who are there for each other in a pinch.

These are people you know and care about. We all understand that the more we put into this, the more we get out.Gretchen Brauer-Rieke

"Every one of us feels extremely grateful to be here," she says, adding that even in normal times, residents watch over each other. They have a "mitzvah squad" to keep track of who is in need of a meal or just someone to talk to.

"These are people you know and care about," Brauer-Rieke says. "We all understand that the more we put into this, the more we get out."

Ann Lehman, a retired lawyer who's now a nonprofit consultant, was craving community as an empty nester and having lost her husband and a sister a few years apart. She spearheaded a tight community when raising her family in California and says, "I realized how much I loved being part of a community while living alone."

Lehman finds it especially appealing to her generation, who grew up in tight communities with strong sets of friends. While there are challenges — she says cohousing often attracts strong personalities that can clash when people live by consensus - it is one antidote to loneliness.

What Lehman most loves is how easy it is to connect: "I like to be spontaneous. It makes a world of difference for me when I can turn to my neighbor and say, 'Do you want to have a cup of coffee?'"

1 Source: Gerontological Society of America, Public Policy & Aging Report, January, 2018. https://academic.oup.com/ppar/article/27/4/127/4782506