Images and story provided by Casey Phillips, Tennessee Aquarium communications specialist

When it comes to a natural ecosystem, the more complex it is — meaning the more animals and plants in it that interdepend on each other — the more fragile it is.

Put simply, says freshwater scientist Dr. Bernie Kuhajda: “The more you have, the more is at risk.”

“If you only live in one cave, one spring or three creeks up on a ridge, it doesn’t take much habitat alteration by humans to completely wipe you out,” he says.

Freshwater biodiversity research at the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute

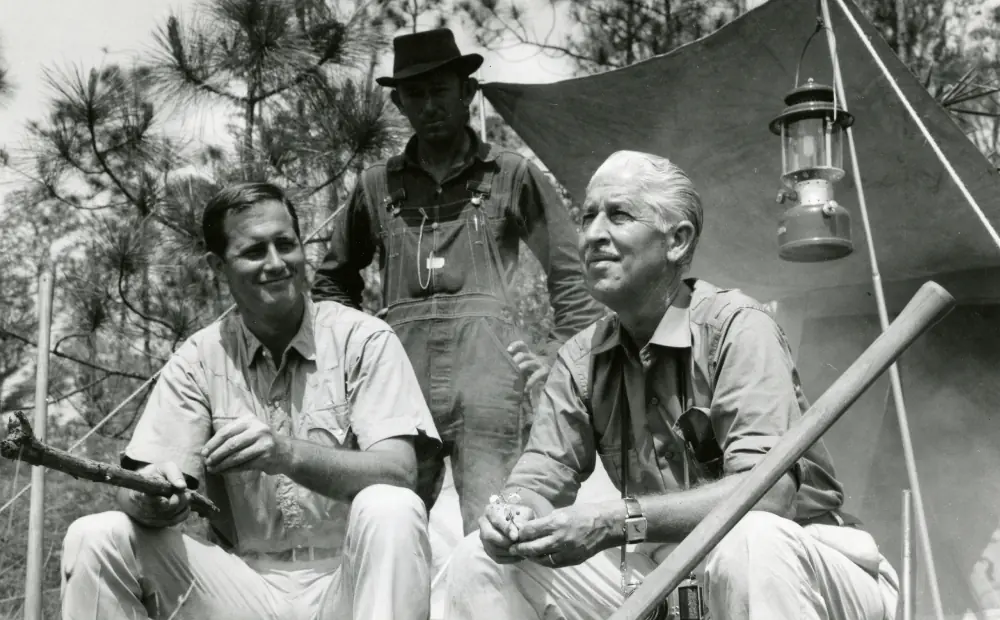

An aquatic conservation biologist at the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute (TNACI) in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Dr. Kuhajda has built a career around studying and protecting imperiled (or soon to be imperiled) species that occupy the richly biodiverse waters of the Southeastern United States.

On one hand, the Southeast is an unparalleled stomping ground for a freshwater scientist.

The TNACI sits at the heart of a region with aquatic diversity unrivaled in the temperate world. More than 1,400 aquatic species reside in waterways within a 500-mile radius of Chattanooga, including about three-quarters (73.1 percent) of all native fish species in the United States. More than 90% of all American mussel and crayfish species live within that same area, as do 80% of North America’s salamander species and half of its turtle species.

How freshwater in the Southeast became diverse

The key to the Southeast’s biological richness is rooted in its uniform climate and diverse geology.

The Southeast wasn’t affected by the glaciation that obliterated aquatic habitat in many parts of North America during the most recent ice age. For millions of years, its landscape has remained relatively stable and wet, which allowed aquatic species to proliferate, Kuhajda says.

In contrast to its relatively humdrum climatic history, the Southeast’s geology is incredibly varied, comprising a patchwork quilt of geologic provinces, large swaths of land defined by a shared geologic structure or features, such as a plain, valley, highland or ridge. Each region’s distinct topography offers habitat to a collection of species that have adapted to thrive there.

“We’ve got all these different kinds of rocks, and in each and every one of those river systems, they have different water chemistry and different fishes, snails, crawdads and mussels,” Kuhajda said. “It really is an amazing place to live, and that’s why I’m here.

“I literally can do research in my backyard.”

Biodiversity leads to a vulnerable ecosystem

Despite the richness of the Southeast’s aquatic life, many species occupy hyper-local habitats, making them even more vulnerable to environmental changes. The Laurel Dace, a focal point for ongoing research at the TNACI, is considered by scientists, such as Kuhajda, to be one of the 10 most endangered fish species in North America and the second most imperiled east of the Mississippi River.

When Kuhajda joined TNACI’s staff 10 years ago, the Laurel Dace could be found in five streams winding their way along a ridge west of Chattanooga. Now, only two streams are known to contain healthy populations.

For animals found in such restricted ranges, any disruption to their habitat — anything that upends the delicate ecological balance that makes their survival possible — can cause a cascade effect on the whole ecosystem. These changes can be catastrophic, possibly wiping out the species entirely.

Why should we care about endangered aquatic species?

When you’re talking about a fish as small as the Laurel Dace or the endangered Barrens Topminnow, either of which would be dwarfed by the average extended index finger, the temptation might be to wonder, “Why does it matter? Why should I care if this animal disappears?”

The answer, Kuhajda said, is that there’s often no way to tell how pivotal an animal’s presence in an ecosystem is or what impact its absence might have. The ripple effect of a species’ removal from the ecological equation could be huge, ultimately affecting humans who might not even have been aware of its existence.

“The most at-risk species are the canaries in the coal mine,” Kuhajda said. “All those aquatic animals form a foundation of an ecosystem that cleans your water for you. Without all those pieces in that foundation, you don’t get as clean of water. Now, you pay more to drink it, you can’t swim in it, and you can’t eat the fish you catch.

“This incredible aquatic biodiversity is important for us and the critters that live in the water. Keeping all these little critters in this river around helps them, and it helps us.”

Intersted in more conservation stories? Read about other organizations that are working hard to conserve the natural world around us.